The rows of vines along my countryside

The rows of vines along my countryside

stretch over fields of clover

that sing with tones of cicadas

and shine with spritely enamels.

Beyond the vines stand white and grey

houses

their shutters amazed. Curious

brows at the edge of a finity

of glassy clusters

with light inside

with warmth inside

of grape-must cradled

in dewdrops of sunlight.

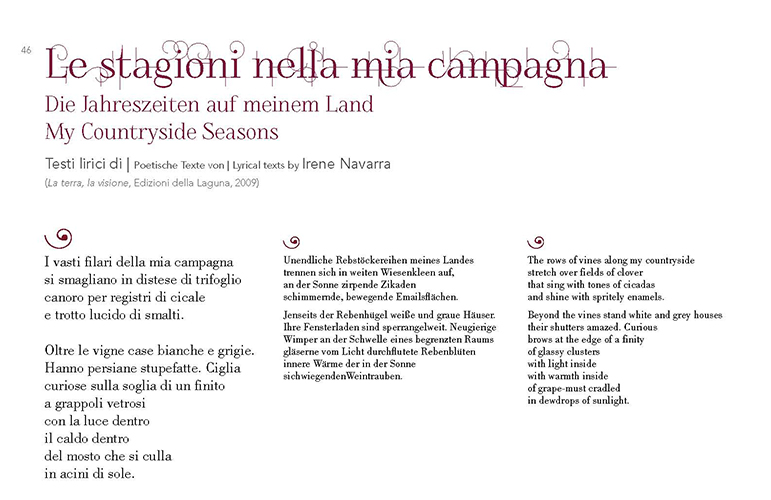

Nelle immagini:

Roberto Faganel, Filari, acquerello, 1992

Roberto Faganel, Tra campi e colli, olio su tela, 2008

Per leggere il testo in italiano e vedere le immagini va' alla seguente pagina del sito:

(From the Introduction to La terra, la visione [The Earth, the Vision], Edizioni della Laguna, 2009)

Ours is a generous land and full of diversity. We see this in the elegant patrician villas or the run-down tinplate shacks, in the paths that cross the fields and in the pebbly trails that lead to the sea along the river Isonzo, with its ever-changing course and colours, reminiscent of battles and human events, faithful companion of our history. We see it in the hidden life of the apple trees and in the mulberry trees, majestic remains of a silkworm farming industry. And we see it in the vast rows of vines that follow one another in the fertile plains of our countryside like benevolent tutelary deities. We can trace then all the way up to the tallest hill, where grapes are not transformed into the friendly nectar that families exchange but scientifically processed and sold to people who may never have set foot here, rode a bike in the hills and shivered at the first gust of bora, people who can’t tell the weather by watching how the clouds group over high ground, people who never sat beneath the walnut trees to watch the vines weep.

The verses of Irene Navarra, like Proust’s madeleines, have the power of evocation. They remind us of the pungent scent of grape-stalks and damp earth, of trunks felled by storms, of persimmons set to ripen together with apples, of walnuts packed in jars with sugar and homemade grappa, of wild flowers, of wet dogs romping in the meadows. All the while presenting us with visions of thin rows of vines clinging to their supports as if carrying the weight of the land, their branches stretched up full of fruit, or crooked and bare like the bodies of the deported, crossed by dirt roads leading to places that no longer exist, telling about dreams of a world without fear, of the labour of man that goes on without end. They are exercises in style and geometric games played on the seasons and their changes. They are symbols that capture thoughts, but without locking them up in the cage of stereotype.

They are expressions of a clear soul, transposed into narrations/invocations that are also a journey of the spirit.

Silvia Valenti